Conducting research in the emergency services and disaster response sector — Exercising empathy and understanding in context.

[

Nailsea Fire station community demo day. The fire and paramedic team attend to a simulated traffic incident.

Guerilla Research

There’s a term in UX research called ‘Guerilla Research’ or ‘Guerilla Usertesting’ which many may be familiar with. This is, essentially when you go out ‘in to the field’, a real space with real human beings going about their daily lives and then ask questions, interview, take pictures, video, sketch and audio record and sometimes even offer a ‘product’ (often a mobile or tablet with wireframes or a physical prototype made of paper, wood or cardboard etc.) for them to test out there and then.

Typically, they don’t have prior knowledge about you and/or your research. You can offer that information in your intro (and I would argue that it’s ethically correct to do so) what you’re typically combining here is an immersive experience of an ‘authentic’ event and contextual enquiry around your subject matter.

Guerilla research is a double-edged sword in my experience as it’s assumed to be cost-saving (for the organisation/company), instantaneous, that it can deliver quality, it’s unstructured and therefore ‘more honest’ and there’s a prevailing assumption that anyone can do it.

These assumptions have multiple risks, directly cost-cheap may be true but there is still a cost to your staff time and in this case of crisis response and emergency services, a risk to their physical and mental safety.

With any sensitive occupation (especially in crisis response and emergency services) There’s a real risk to the research subject in terms of their career safety, mental health and emotional health. These folks could really be risking their livelihood to offer you ‘non-text book’ answers to your questions and on the extreme side could be under non-disclosure agreements around specific incidents.

Unsurprisingly to some, it’s not always very insightful or high ‘quality research’. This can be for a number of reasons, from the complex that your interviewee may speak in terminology that you have little context or sector vocabulary for or they could simply refuse to speak to you.

It also assumes that you’ll find your ‘target audience’ locally and for zero incentive. Finding and staying in these situations often leaves me with a sense of trespassing. I often have visualised a timer on a situation where I feel like I’ve outstayed my welcome. I’ve also been asked explicitly whether I was ‘from the media’ or ‘press’, to which the answer is officially ‘no’ but there are no guarantees or protections for those interviewees.

Much like anything else, it’s true that anyone can perform the actions of guerilla research but that doesn’t mean you’ll get meaningful interactions, answers or results. Even if you’re a UX professional with years of experience. Guerilla research/testing is often an exercise in hard to define skills. Like your ability to ease into new situations, your adaptability, your overall charm and persuasion skills and of course, your ethics in executing these skills. Just because you could extract insight from a person does it mean you should?

Ushahidi and Crisis response research

Working at Ushahidi, we’re focusing on innovations and design that improve the systems of communication in crises, from both the communities experiencing incidents and the people involved in responding to them. Long or short term with an emphasis on real people advocating for their needs and boosting that signal all the way up. Nobody knows the needs of people across the globe experiencing a disaster or incident better than those experiencing an event there and then or the people responding to it.

As a team of two designer/researchers we have to work lean as time and resources for lengthy discovery phases don’t come along often. The time it takes to plan a research effort doesn’t always fall in line with optimal research parameters. The world of crisis response either moves slowly and incredibly fast. The slow periods tend to have an emphasis on monitoring, resilience building, training and preparing which is a different environment to enter than a live incident or crisis.

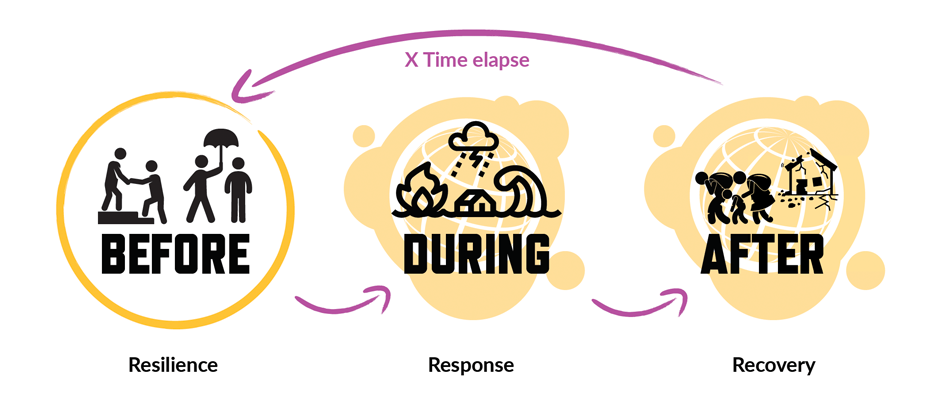

[

An illustration of the lifecycle of a crisis: Resilience, Response and Recovery. With icons from Flat Icon

One of the ways my design partner (Justin Scherer) and I have been researching crisis is observing simulation exercises and asking those that work in a form of emergency response, incidents and crises about their roles, past incidents and current lives.

This involves both community-based led efforts like SARAID (Search and Rescue Assistance in Disasters), CRT(Community Resilience Team) and Team Rubicon and our uniformed service people like the fire service and police service as well as relief organisations based at fire and rescue centres like the Red Cross and any governmental/UN-based first responders.

So in the spirit of ‘Guerilla’ style research, How do you communicate your purpose without putting people off?

At Hicks Gate Fire Station I attended an incident demonstration day. I observed, asked questions about what was being done and progressively asked more complex questions about the needs of both emergency service workers and ‘victims’ of an incident. After speaking with a London Fire Service person who mentioned that after Grenfell, what they could say was understandably limited and they genuinely feared for their livelihood and reputation. I was told to call the media relations team several times.

I wonder how effective the insight media relations team could offer?

How sanitised would the information be?

Or would you be offered interview time with the emergency service people, only to discover that they have been briefed on what to say and what not to say?

If someone believed that I wasn’t from the media, the next answer was that I was attempting to sell them technology services.

Several people were (understandably) hesitant to speak to me, especially when I had my audio recorder in hand. Questions about your publicly funded job (wherever these services are publicly funded and not privately funded) are sensitive. No level of communicating my purpose as a fellow person within the incident management sector (albeit the tech side) could adequately convince some people that my intentions were honourable.

Regardless of the hurdles, I gathered deeper insight, experience and anecdotal evidence on the workings (specifically the technology-related ones) of the emergency services and identified some key areas where technological intervention could make first responders more effective.

But how applicable was this insight to global crisis and disaster response? Likely not very applicable given the social and country-specific contexts needed to understand how a nation’s citizens respond to crisis.

But there was still the question of, how do you get a real understanding of an incident outside of experiencing a real one?

[

The Urban Search and Rescue team based at Hicks Gate fire station in Keynsham run a simulation moving large pieces of concrete with new equipment and in the background, a second-team drill through a cement obstacle.

Deeply embedded ethnographic research

After the guerilla approach to this subject, we very quickly discovered that taking a ‘dip in dip out’ approach to this work was only going to offer us the surface-level insights into human responses to crises that were specific to those circumstances and to gather a better understanding of country-specific needs that could then potentially be generalised further research globally needed to be conducted. We wanted to design solutions for deeper human reasons for helping others.

We also needed to explore what ‘temporal’ design research would do for us in this field and what an ‘invested’ design could do for us. As a team of two, we leaned naturally in different directions, myself in the direction of long term relationships that build understanding through a connection and Justin in a well defined ‘researcher to subject’ relationship. Both approaches have benefits and pitfalls, for example, long relationships require a genuine interest that is next to impossible to feign and the real risks of not following through in that relationship but potential gaining a spectrum of insights on human responses to a research topic. Short relationships can, if the conditions are right, offer you the same quality of insight as a long relationship in a shorter space of time and can be more targeted early on but you risk the flip side being very little information of quality if a person does not trust you.

We decided to test each approach in an even split between us two design researchers with participants at a field research study based in Nairobi, Kenya. However, this field study was focused on the community level response to crisis rather than the official services. You can find more detail about the ‘Dispatcher pilot’ via a slide deck of a talk called ‘Designing for Crisis’ via Notist (transcription is WIP as of Dec 2019)

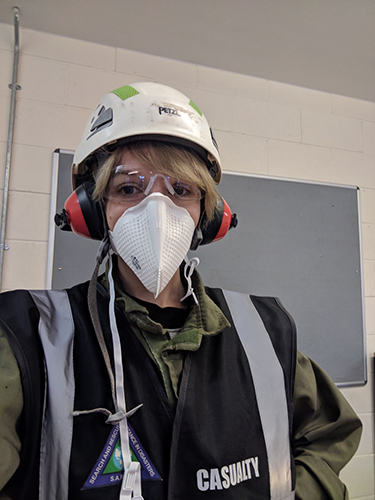

[

Photo of Eriol Fox (Author of this article and design researcher) as a casualty on a search and rescue training exercise in the UK for the IRT division of SARAID.

Conducting field research which is empathetic to your user base test case

My personal conclusion to research into the crisis response, disaster relief and emergency service sector is that the volunteer organisations are generally welcoming but only if you’re interested in long term involvement. This could be long term mutually beneficial research activities or that you become part of the volunteer organisation. I chose three volunteer organisations to invest my time and efforts in the post-research phase due to active and genuine interest. This also allows me to practice my approach to research which is more embedded and integrated.

The emergency services are harder and they should be. I was able to have a handful of candid conversations with current and ex-emergency services employees and I was very explicit with myself (and them if they asked) that if any of the information was to be ‘used’ to inform design and/or approaches to solving problems in the sector then I fully abstracted that information from that individual and took it on as my own responsibility to protect.

Please look out for part two of this article series on crisis response and disaster relief design research.

-Eriol Fox